The Archaeological Museum at Iraklion has a rich collection of Bronze-Age artefacts that is spread out across a large number of interconnected rooms on the building’s ground floor. One room dedicated to the Neopalatial phase, the zenith of Minoan civilization, features a large display case that is empty save for a small round object – a clay disc – held in a metal brace.

When I was in the museum last July, I nearly overlooked this display case. I wasn’t the only one. I actually observed other visitors, who moved from display case to display case, before skipping the one with the clay disc and moving to another room. That’s a pity, because they missed out on one of the more curious artefacts that the early Cretans produced.

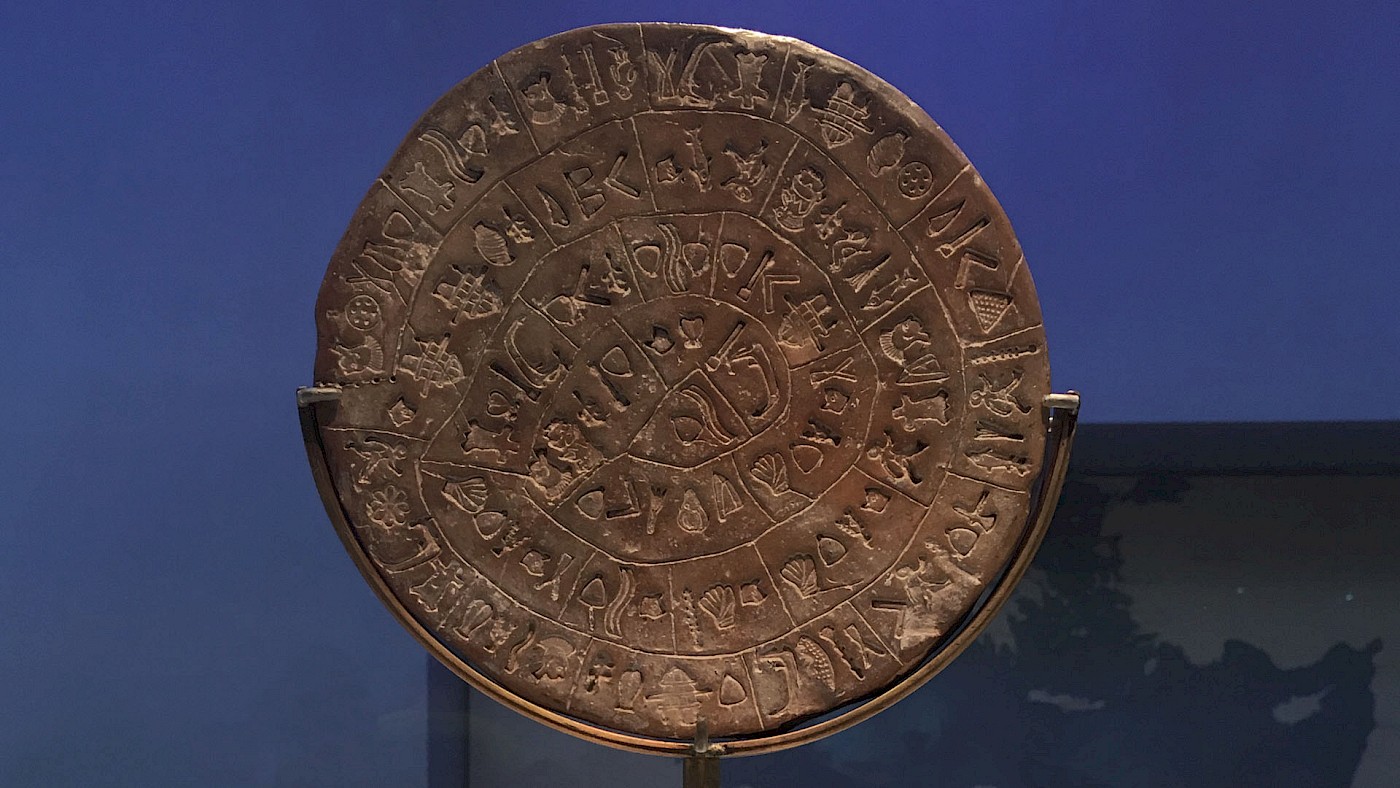

This clay disc, measuring about 15 cm in diameter, was recovered from the northeast corner of the palace at Phaistos, and is known as the “Phaistos Disc”. The findspot is marked on the archaeological site with a sign, even if it’s not immediately clear in which of the rooms the disc was found. The two sides of the disc are similar: each features a large number of symbols arranged in a spiral, with groups of symbols separated from each other using vertical lines (to mark words), with the final symbol in such a group sometimes being marked by an oblique stroke, perhaps to mark the end of a phrase. (For details, refer to the works by Yves Duhoux listed in the references.)

There has been much debate about the Phaistos Disc. What seems clear is that the symbols are some kind of writing, with vertical lines perhaps used to group symbols together into words. But the writing system is different from the other three forms of writing found in Bronze-Age Crete (hieroglyphic, Linear A, and Linear B). The two sides of the disc feature 45 different symbols in total.

Similar symbols are also found inscribed on a bronze double-axe from a cave at Arkalochori (which is also on display at the museum), alongside symbols that seem to derive from Linear A. If the Phaistos Disc-like symbols are part of the same system, the total number of unique symbols is increased by 7, bringing the total number to 52. As such, it’s most likely another form of syllabic writing. (Whittaker 2005 suggests the Phaistos Disc is actually an example of pseudo-writing.) Alphabetic writing doesn’t need more than about 20 to 30 symbols in total, whereas true hieroglyphic writing requires hundreds of symbols.

The interesting thing about the symbols on the Phaistos Disc is that they were not individually inscribed, but rather stamped (pressed) into the clay. In other words, someone went through the trouble of making a (metal) die for every symbol, making the Phaistos Disc the earliest known example for the use of “moveable type”. This suggests that the Phaistos Disc, or at least its inscription, was some kind of mass-produced object, yet nothing else like it has so far been unearthed.

We have no idea what the symbols mean. What seems obvious, however, is that the texts had to be read from the exterior inwards. If you look along the other edge of each side of the disc, you’ll see an obvious place where you’re supposed to start reading: a line marked with points pushed deep into the clay. On side A, the first two symbols are the head of a man and a round object that is either a shield or – perhaps more likely? – a round flatbread. On side B, the first two symbols are the same, but the group (marked by a dividing line) features a number of other symbols, too.

According to John Younger and Paul Rehak (2008, p. 177):

Arranging the words by their apparent phrases (the oblique strokes), we can see that both sides end with similar series of phrases. The phrases on side A begin with similar signs, and those on side B end in similar signs, suggesting repetitious phrases on A and rhyming phrases on B. For these reasons, it is likely that the Phaistos Disc records a poem or song, or, if it is religious, as some suppose, a chant or hymn.

As with Linear A and Cretan hieroglyphic, there have been many, many attempts made at desciphering the meaning of the symbols on the Phaistos Disc. Such attempts are unlikely to be successful, however. We don’t know exactly what language the Cretans spoke in the Bronze Age, and the amount of texts that has survived to the present day is simply insufficient to make any strong pronouncements as to even what language family “Minoan” might have belonged to, or even if there was just one language.

Whatever the meaning of it symbols, the Phaistos Disc is a remarkable object and well worth checking out for yourself. So if you find yourself in the Archaeological Museum, keep your eyes peeled for a display case that appears, at first blush, to be empty. You can find it in one of the rooms towards the back of the exhibition area on the ground floor.

And before I leave you, Prof. Louise A. Hitchcock pointed out on Twitter that Dr Brent Davis recently (2018) looked at the symbols on the Phaistos Disc. A statistical analysis comparing the symbols on the Disc with Linear A suggests that both were used to write the same language.

Further reading

- Brent Davis, “The Phaistos Disk: a new way of viewing the language behind the script”, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 37.4 (2018), pp. 373-410.

- Yves Duhoux, Le Disque de Phaestos (1977).

- Yves Duhoux, “L’écriture et le texte du disque de Phaistos”, in: Pepragmena tou 4. Diethnous Krètologikou Synedriou (1980-1981), pp. 112-136.

- Helène Whittaker, “Social and symbolic aspects of Minoan writing”, European Journal of Archaeology 8.1 (2005), pp. 29-41.

- John Younger, “The Aegean bard: evidence for sound and song”, in: S.P. Morris and R. Laffineur (eds), EPOS: Reconsidering Greek Epic and Aegean Bronze Age Archaeology (2007), vol. 1, pp. 71-78.

- John Younger and Paul Rehak, “Minoan culture: religion, burial customs, and administration”, in: Cynthia Shelmerdine (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age (2008), pp. 165-185.