Born perhaps in AD 1313, Giovani Boccaccio was a prolific writer of fourteenth-century Italy. Like many of his contemporaries, he was deeply versed in the literature of the ancient world.

One of the best-known Medieval works on ancient mythology, the Genealogia deorum gentilium (On the Genealogy of the Gods of the Gentiles), was scribed by his hand, with the first version finished in AD 1360.

But hidden away in one of the hundred stories of his Decameron is the retelling of a relatively minor story found in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses. Importantly, it is not a story about the gods, or about powerful mortals in lofty positions.

Apuleius’ Metamorphoses

Apuleius was a writer and orator, born in AD 125 at Madaurus, in Africa. He is, perhaps, known to most readers as the author of the only wholly surviving Latin novel from antiquity. This is titled variably as Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass. (For an overview of his life and works, see The Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. Apuleius.)

In the ninth book of the Metamorphoses, we hear the tales of the Baker’s Wife and the Fuller’s Wife. The former is part of the main narrative, while the latter is told by the baker, humorously as we shall see, whilst his wife was trying to hide her lover. The baker and fuller were to sup together on the evening being narrated, but when they went to clean up they disturbed the latter’s wife and her adulterous partner.

She hurried him into a hiding place, which happened to be something of a drying rack for clothing being cleaned with sulfurous smoke. Although the wife’s lover may have been hidden from sight, this was not an ideal place to stay. The fumes from his surroundings made him sneeze. The first of these was thought by the fuller to have come from his wife, but as it continued the husband grew suspicious.

He went to where his cuckolder was cowering and revealed him. Seeing now that his wife was certainly cheating on him, he began to rage and wanted to kill the young man. The baker, however, warned against this, saying that the fumes that the adulterer had inhaled would do the job anyway, without the fuller having to dirty his hands. So the knave was thrown out of the house, and the two friends retired to the baker’s house, thinking that a cooling off period would help the fuller.

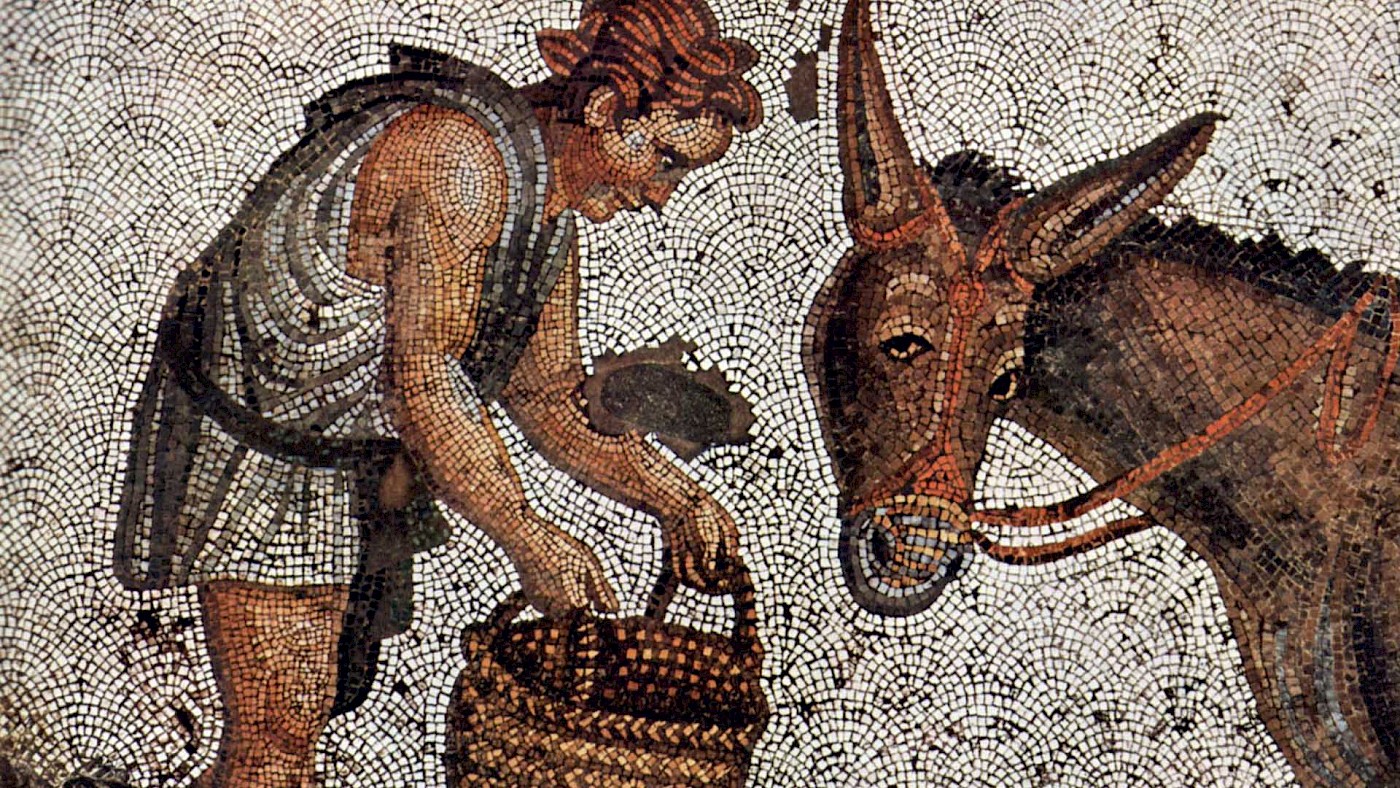

Of course, this is what caused them to interrupt the baker’s wife and her own love rat. Having heard the story told by her husband, she began to curse the unfaithful woman and wives in general. Seeing this and being disgusted at the hurt being visited upon his master, the ass (Lucius), who is the novel’s protagonist, kicks the adulterous youth in his hand, causing him to cry out and his hiding place to be found.

The baker assures his wife’s lover that he is not going to kill him, even though it is within his rights, but instead wants to bring all three of them together in bed to sort out an arrangement. When they all go to bed, the wife is led to another room. In the morning, the baker whips the young man on his buttocks and then sends him packing. His cheating wife he divorces, who then engages the services of a witch to kill her now ex-husband. An evil spirit is summoned and somehow – we don’t hear the details – kills the baker by hanging, perhaps meant to look like a suicide.

Boccaccio’s retelling

Boccaccio’s version of this tale is the tenth story being told on the fifth day of the Decameron. For those unfamiliar with this Renaissance masterpiece, it is a collection of one hundred stories, all told through a framing tale set in Florence during the Black Death. There are ten narrators, who each tell one tale per day for ten days.

Narrating this particular story is Dioneo, one of the three young men in the group. From the start, his version differs a bit from that found in Apuleius. Rather than being a baker, the main character is described as “a rich man” and we actually get his name, Pietro di Vinciolo, from Perugia. (All quotations from the text are taken from G.H. McWilliam’s 1972 translation, as published in the 1979 Franklin Library edition.) Boccaccio also foreshadows the ending of the story, telling us that Pietro “perhaps to pull the wool over the eyes of his fellow citizens or to improve the low opinion they had of him, rather than because of any real wish to marry, took to himself a wife” (p. 393).

As we shall later learn, this was indeed mostly to protect his own reputation. In doing so, he went to the extreme, finding an eligible “buxom young woman with red hair and a passionate nature.” We hear a bit about the marriage while the young wife is discussing her lack of sexual contact with her husband with an outwardly saintly old woman.

The elder speaker agrees that the young woman should look beyond her husband’s services for her own sexual gratification. She legitimizes this through a number of arguments, extremely antiquated and very sexist by our modern standards. For example, she declares that “women exist for no other purpose than to [fuck] and to bear children” (op. cit., p. 394). Continually in the introductory section we are made to believe that the unrequitedly horny wife cannot cope with being married to a closeted gay man.

The buxom redhead then begins to regularly bring young men to her chambers, with the aid of the old woman to whom she gives a joint of salted meat as payment, a delicious detail not found in Apuleius.

However, on the fateful night which makes the story, Pietro found himself coming home early from supper with his friend Ercolano for exactly the same reason that the baker and the fuller returned to the former’s home early. As the pair sat down to eat with Ercolano’s wife, sneezing began to come from a cupboard. His wife had explained the sulfurous smell as being the result of her bleaching her veils earlier in the day. Upon opening the cabinet, though, they found her lover!

After Pietro told his wife this story, she cursed all women like her, just had the baker’s wife. “So help me God, women of her kind should be shown no mercy; they ought to be done away with; they ought to be burned alive and reduced to ashes” (op. cit., p. 397). Again, these are the cries of a guilty conscience.

When her husband had knocked to be let into the house, she had hidden her love in a chicken coop which adjoined the kitchen/dining room. Although the fire-haired beauty attempted to hurry Pietro to bed upon his arrival, he insisted on eating something first. Before he could be fed his supper, however, a thirsty ass which had broken its tether in the shed just outside the house stepped on the hand of the young man hidden in the chicken coop.

He let out a cry and was discovered by the wealthy Perugian. Pietro went to investigate, and to his surprise, “recognized the young man as one he had long been pursuing for his own wicked ends” (op. cit., p. 398). Chastising his wife for lamenting Ercolano’s so profusely, she counters by saying that “you’re as fond of women as a dog is fond of a beating.” They go on to argue about his homosexuality and her sexual needs. They agreed to sit down, the three of them, for a meal.

Dioneo conveniently forgot how the three resolved to remedy the situation, but only that the young man “was found next morning wandering about the piazza, not exactly certain with which of the pair he had spent the greater part of the night, the wife or the husband.” He closes his tale with a suggestion for the ladies in his party: “you should always give back as much as you receive; and if you can’t do it at once, bear it in mind till you can, so that what you lose on the merry-go-round, you can make up on the swings” (op. cit., p. 399).

Conclusions

The similarities between the version of the stories presented by Apuleius and by Boccaccio leave no doubt that the latter was familiar with the works of the former. Certainly, Apuleius was known again in Italy by the early fourteenth century. The text of the Metamorphoses may have been “found” by Benzo d’Alessandria, who claims as much in a piece written between 1312 and 1322 (R.H.F. Carver, The Protean Ass: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius from Antiquity to the Renaissance (2008), pp. 112-113).

Interestingly, there was a story that Boccaccio himself had discovered the text of Apuleius by smuggling (stealing) a codex out of the abbey at Monte Cassino (Carver 2008, pp. 108-112). This is probably not true, but he definitely did have access to the text. And though he certainly used Apuleius’ stories as a basis for those put in the mouth of Dioneo, what is important to note is that in the Renaissance retelling, certain details were changed to make the story have a different moral message.

In Apuleius, we hear of mischievous women, driven by their sexual desires to be unfaithful to their husbands. Lucius, the ass, is sympathetic to his master who is being cheated on. In Boccaccio, however, we are being told about the immorality of gay men, with the narrator emphasizing his view that this was unnatural behavior. Thomas Bergin noted the exceptional fact that Pietro is the only “sodomite in the cast of characters” across all one hundred stories (T.G. Bergin, Boccaccio (1981), p. 312).

Thus, in the end, we have read two versions of the same story, each with a very different message. In the ancient tale we learn of the licentiousness of women, whose actions are hurtful towards their husbands. In the Renaissance telling, however, we hear about the immorality of homosexuality and the rightful sexual needs of young women, which should be explored even if their husband’s interest lies elsewhere.

While perhaps none of the messages resonate with us today, it is quite interesting to see how an ancient story can be recycled to reflect the changing morality of human society.