When the Greeks decided to start “colonizing” the central Mediterranean – essentially southern Italy and Sicily – they were beset by warlike neighbors. This struggle lasted for much of these poleis’ individual existences. Or so we are generally led to believe. The interactions between early Hellenic settlers and Italic and Etruscan people was almost certainly rather peaceful and oriented towards mutually beneficial trade.

But in the long run, this was not a politically profitable situation for rulers in Magna Graecia (Great Greece), as this zone of Greek settlement became known. War against Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Etruscans, and Italic peoples was used as an excuse to bolster the power of tyrants, launch piratical raids, and posture in the pan-Mediterranean game of political arete. Whether because of the interlopers’ actions or because the people already living around the Tyrrhenian Sea were themselves aggressive, conflict became the norm, or at least rather frequent.

Although we hear of earlier battles with some level of detail, notably the Battle of Alalia (styled by some as the Battle of the Sardinian Sea), the end of the second decade of the fifth century BC was the beginning of major conflicts between Greeks and others in the central Mediterranean. In 480 BC, a large army was brought to Sicily by the Carthaginians, at the behest of a number of allied Greek tyrants, to attack Himera and restore Terillus to power. Although this was not a “barbarians versus Hellenes” situation, as the supposed barbarian side was built on a foundation of Greek leadership, it was portrayed by the victor as such.

Countering this “invading” force was Gelon tyrant of Syracuse, as well as Theron of Acragas, and their armies. As we hear in our sources (primarily Herodotus), they won a crushing victory that would be equated to the Aegean-Greek victory over the Persians in the same year (Hdt. 7.165-167; Krings 1998, pp. 261-326). Of course, this was framed in a way to explain why the extremely wealthy and powerful tyrant of Syracuse had not given aid to his Greek cousins in their fight against the Median enemy.

The Battle of Cumae

Gelon’s brother and successor would win a victory in 474 BC that would be framed in the same way, though through a complex set of pan-Hellenic maneuvers designed to enhance his position and legacy. In this year, a conflict between an unknown group of Etruscan peoples (or at least Turrênoi according to Diodorus) and the Italiote Greek city of Cumae came to a head in the waters off that city.

Hiero, the new power in Syracuse, sent a large fleet to aid the Hellenes and won a supposedly great victory over the enemy (Diod. Sic. 11.51). Although this was a significant battle, at least as we see it through Deinomenid eyes (explained below), the idea that it single-handedly broke some sort of Etruscan thalassocracy is almost certainly ill-founded.

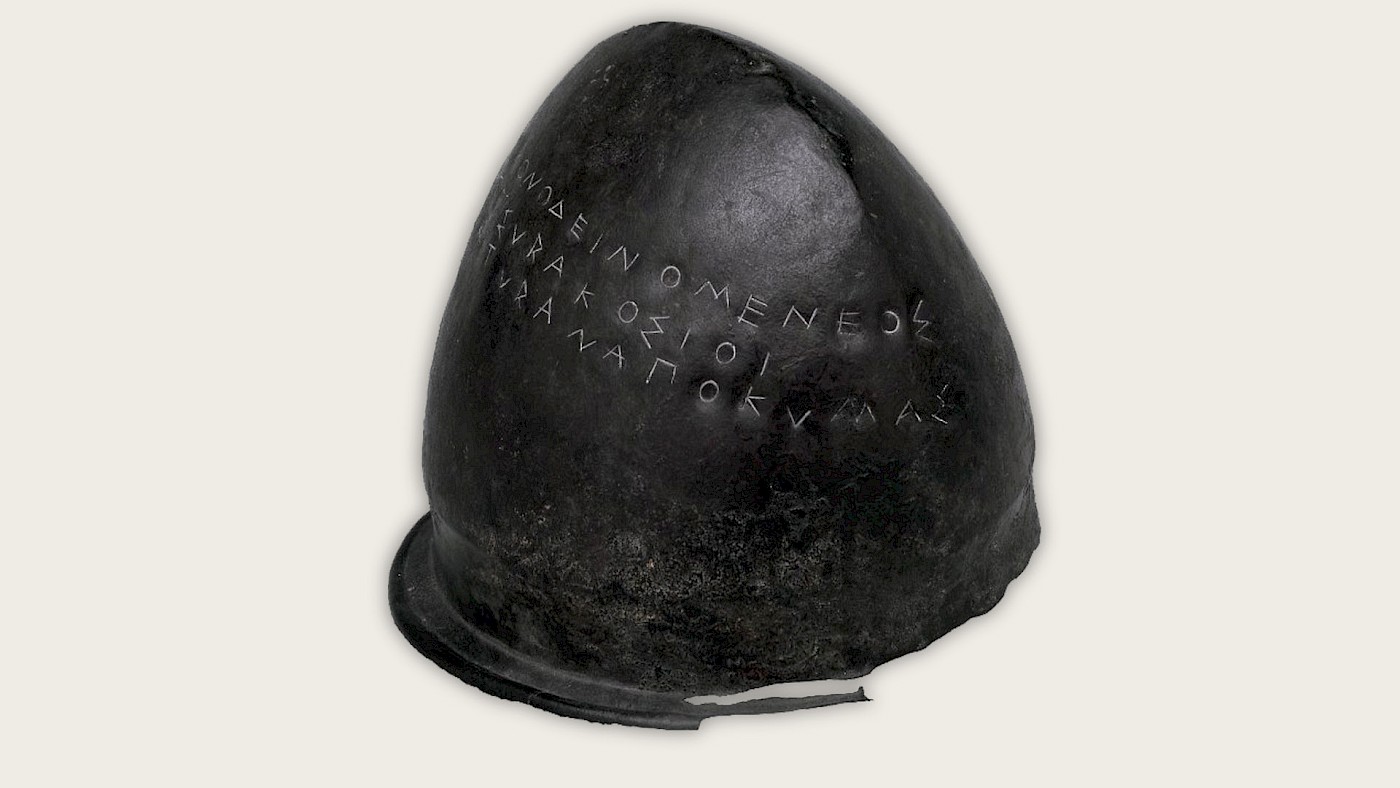

In the wake of this victory, Hieron publicized it in no less spectacular means than a modern leader would celebrate a minor military victory through the news media and their own propaganda machine. Three helmets were dedicated at Olympia to announce the triumph to anyone who came to the sanctuary complex (Bröndsted 1820; Linagouras 1979; Frielinghaus 2011, L1 and L2, 70-71, 448). On these was inscribed (tr. Whitley 2011, p. 185):

Hiaron [the son] of Deinomenes and the Syracusans to Zeus [dedicated these arms captured from] the Tyrrhenians at Kyme (Cumae).

There was no mistaking whose victory this was. Although Hieron proclaimed it in both his name as well as that of the Syracusans, a Greek reading this inscription would have almost certainly seen between the lines and known that this was the tyrant’s victory that was being celebrated, much in the same way that Dionysius I used “the Syracusans” as a way of legitimating himself in treaties with Athens in the fourth century BC. Dedications in a pan-Hellenic sanctuary was also in-line with his brother’s practice after Himera (Paus. 6.19.7; Morgan 2015, 30-45). Though, we should not entirely remove the polis from these dedications, as Neer and Kurke have recently described the treasuries at panhellenic sanctuaries, they were built “not just to store votives but to nationalize them,” but at the same time they connected “a dedicant’s [like Hieron’s] privileged relationship to the gods” (Neer and Kurke 2019, 248).

Nevertheless, these helmets were not the only way that Hieron celebrated – and exploited – his victory at Cumae. The tyrant might have setup a tripod and Nike at Delphi (Morgan 2015, 41-5), but he undoubtedly commissioned the great poet Pindar to immortalize his accomplishment in what we know as the latter’s First Pythian Ode (71-80; tr. Verity 2007, p. 44):

I pray you, son of Cronus, grant that the war-cry of Phoenicians and Etruscans / May stay at home, now that they have seen their insolent violence / Bring lamentation on their fleet for what it endured at Cumae / crushed by the Syracusan commander, who hurled their finest men / from their swift ships into the sea, and rescued Greece from harsh slavery / From Salamis I shall earn the Athenians’ thanks as payment / and in Sparta for my tale of the battles before Cithaeron / where the Medes who shoot with curved bows were overcome. / But by the well-watered bank of Himera / my reward shall be for the song I have made for Deinomenes’ sons / which they earned by their courage when their enemies were overthrown.

In this we see that the Battle of Cumae is being deliberately associated with that of Himera, and these are then tied back to the Greek struggle against the Persians. As Kathryn Morgan has pointed out, “when Pindar describes Hieron’s naval victory (…) he uses language that resonates immediately for anyone familiar with the Persian Wars” (Morgan 2015, p. 155). From a modern perspective, we would say that this was a deliberate propaganda campaign to bolster the position of the Syracusan tyrant on an international stage (cf. Prag 2010).

And this is exactly what Hieron was doing. At home he was in a relatively secure position, perhaps even more so if he really did enhance the Temple of Athena in Syracuse after the battle (De Angelis 2016, pp. 103 and 188). But, it was in the eyes of other Greeks and the “international” community as a whole that he was trying to prove himself with these dedications and poetic patronage.

Closing thoughts

Although there is considerable analysis and discussion to be had on this topic (and it is ongoing in scholarly literature), there is a single – if glib – lesson to take from it. The Mediterranean world of the fifth century BC, at least amongst the Greeks, was very much a “global” world.

Of course by this I don’t mean that the entire Earth was involved, but almost certainly all of the “known” world was engaged. This is important to keep in mind when we think about the longue durée of celebrating military “victories”. Those who shout the loudest about their triumphs are often those in precarious positions, on either their local or the international level, and use these as a means of stabilizing their power.

Perhaps the real Hieron was as afraid of losing his power as his namesake doppelganger in Xenophon’s Hiero the Tyrant, who didn’t like the idea of going “to places where he [a tyrant] would be no stronger than anyone else” (Xen. Hier. 1.12; tr. Waterfield 1997).

This seems rather likely, and of course Hiero and his siblings were no different than other Greeks in looking to secure their position in the Mediterranean world through dedications at pan-Hellenic (though more properly pan-Mediterranean) sanctuaries and through high-profile Greek poets and playwrights. More broadly, though, this gives us an idea of how far back the use of military force to bolster the political position of an individual goes, and should help legitimize our critique of such actions.

Further reading

- P.O. Bröndsted, Sopra un’iscrizione greca scolpita su un antico elmo di bronzo rinvenuto nelle ruine di Olimpia del Peloponneso (1820).

- F. De Angelis, Archaic and Classical Greek Sicily: A Social and Economic History (2016).

- H. Firelinghaus, Die Helme von Olympia (2011).

- V. Krings, Carthage et les Grecs c. 580-480 av. J.-C. (1998).

- A. Linagrouas, “Ηλεϊα – τυχαϊα ευρήματα,” Archaiologikon Deltion. Meros B Chronika 29 (1979), pp. 342-344.

- K. Morgan, Pindar and the Construction of Syracusan Monarchy in the Fifth Century BC. (2015).

- R. Neer and L. Kurke, Pindar, Song, and Space: Towards a Lyric Archaeology (2019).

- J. Prag, “Tyrannizing Sicily: The despots who cried ‘Carthage!’,” in: A. Turner, K.O. Chong-Gossard, and F. Vervaet (eds.), Private and Public Lies: The Discourse of Despotism and Deceit in the Graeco-Roman World (2010), pp. 51-71.

- J. Whitley, “Hybris and nike: agency, victory and commemoration in Panhellenic sanctuaries,” in: S. Lambert (ed.), Sociable Man: Essays on Ancient Greek social behavior, in honour of Nick Fisher (2011), pp. 161-91.