With the COVID pandemic still in full swing, it has been very hard to get into museums and see their collections. I was booked into Manchester Museum back in April 2020, to view an exquisite black figure vase up close and personal – in what would have been my first ever experience of seeing a vase without a glass barrier in the way, I might add!

But, alas, it was not meant to be. With the lockdowns, surging rates of cases, and working from home initiatives, I am still unable to view that vase.

However, in the Internet Age we can find ways around these problems. I can still not get close to it, but the reason I wanted to see it in the first place was because all of the available images online and in books were of such poor quality. I recently emailed the team at the Manchester Museum and asked if I could see a better quality of image and they were nothing but obliging, supportive and helpful from start to end.

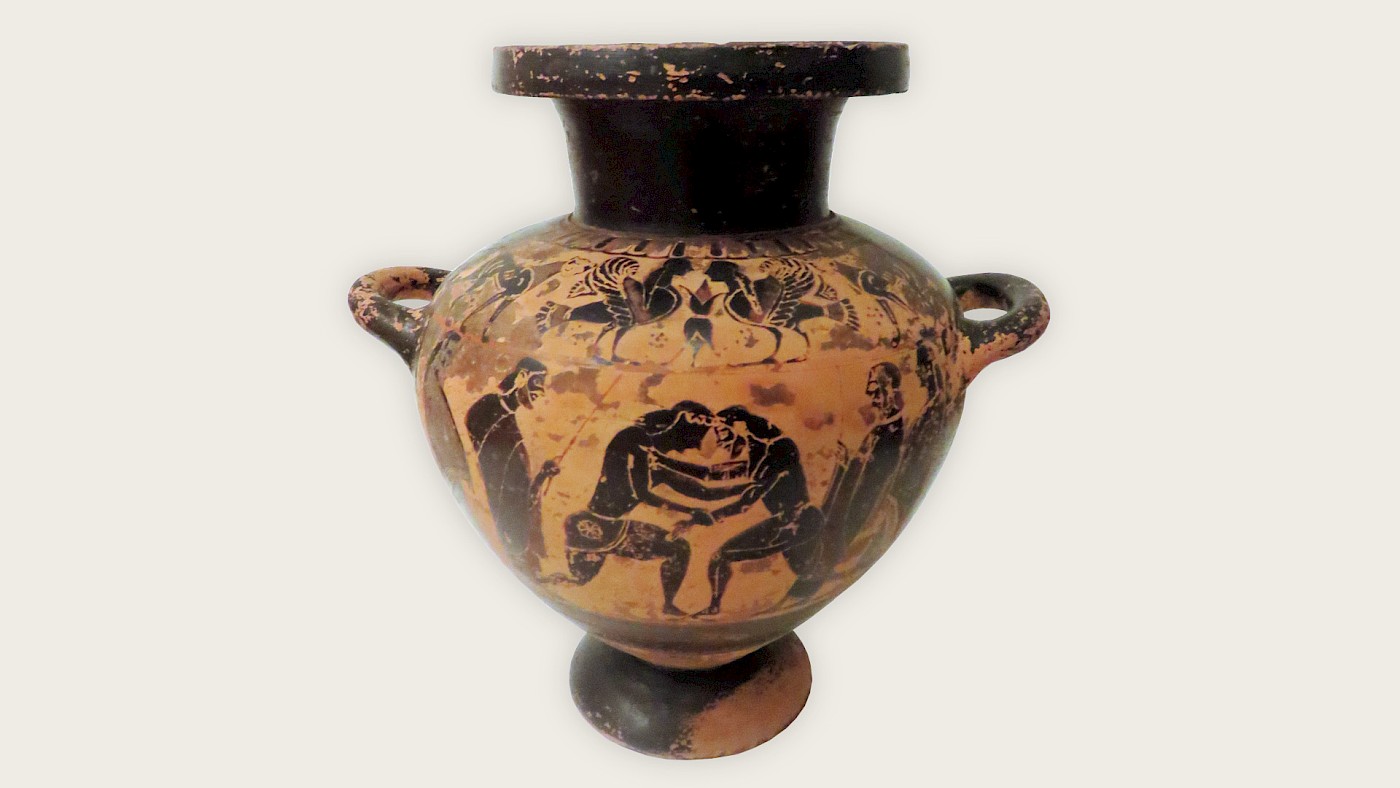

The vase in question is at the top of this article. It is a black-figure hydria, dating from the sixth century BCE. The painter is unknown but has been attributed by scholars to the Atalante Group due to its artistic style. Our editor-in-chief Josho wrote an earlier article on connoisseurship and its problems.

The scene is a relatively common one, the hero Atalanta on the left is wrestling a man on the right, with a few male and female spectators on either side. The male wrestler is most likely the Argonaut, Peleus, father to the hero of the Trojan War Achilles. The mythical context is well attested, but poorly described in the textual sources. Our main source, Pseudo-Apollodorus, is frustratingly bereft of detail (3.9.2):

at the games held in honor of Pelias she wrestled with Peleus and won.

The details of the fight are non-existent, all we are told is that she won. It seems female athletes have never been given the column space they deserve!

The image of Atalanta wrestling with a man was a popular one for Greek vase painters, offering as it does a beautiful contrast between the male and female form. In what is known as black-figure pottery, women are usually portrayed with bright white skin added on top of the black paint, as opposed to the skin of men, which is left black.

Normally, with Atalanta and Peleus, the contrast of dress (men trained and competed in complete nudity, women were clothed), of hair style, of anatomical form, is highlighted by the bright white of Atalanta’s skin. But on this vase, this is clearly not the case and makes it all the more intriguing.

It depicts Atalanta and Peleus wrestling, but Atalanta has not been given white skin. The identification as female is still easily assigned, however. She is half dressed in a loose loincloth; she has a female hairstyle; her musculature is purposefully ill-defined compared to Peleus’. Yet, the choice of the artist to represent her superficially as equal to Peleus – as male in all but form – is remarkable.

Atalanta was always a hero who broke gender stereotypes. She went on the legendary hunt for the Calydonian boar, alongside other heroes like Jason and Theseus – she was even the first to draw blood from the beast and was awarded the skin as her prize, much to the ire of some of the young men present.

According to at least one tradition, Atalanta was also chosen as one of the Argonauts to travel with Jason on his quest for the Golden Fleece (Pseudo-Apollodorus, Library, 1.9.16.). However, our main version of the story, Apollonius’ Argonautica, states that Jason refused her request to join the expedition as her presence would cause strife among the men (1. 768).

On this vase, the image encourages us to see the two wrestlers as equals. The two heroes are in a mirrored posture, with one knee close to the floor in a contest of strength it seems. This is a contest Atalanta should lose against the more muscular Peleus.

But, as your eyes come to the centre of the scene you can see that Atalanta, on the left, has control. Her hand clasps the wrist of Peleus, dragging his arm down to initiate a throw, or perhaps blocking his hand from taking a surer grip. Her victory comes, not from brute strength and aggression, but through skill and fortitude. This mythical scene fits wider Greek ideas of wrestling as a skilful combat sport.

According to Pausanias, it was Theseus himself who turned wrestling into a contest of skill (1.39.3):

For Theseus was the first to discover the art of wrestling, and through him afterwards was established the teaching of the art. Before him men used in wrestling only size and strength of body.

Wrestling has always been a thinking person’s sport. In the modern day, athletes are separated into weight categories to allow for fairer contests, but the ancient world did not allow for the luxury of a fair match. To be the best you needed to beat anyone who stood against you.

So, for it to be worth competing as a smaller athlete, or in Atalanta’s case as a woman, there must have been more to the sport than just physical strength. It is just a shame that Greek writers did not feel the need to spend longer on telling the story of her victory. A shame, but not a surprise.